Original is SOLD. Prints and canvas reproductions available here.

I like to think of myself as an optimistic person. After all, I am a lifelong Cubs fan who always believed in the hope-filled power of next year. Then again, when they lose three games in a row these days, feeling certain that they’ll never win another game again seems pretty pessimistic.

The truth is, I’m probably a little bit of both.

The optimistic side of me believed that Penguins Can’t Fly would be a New York Times best seller. It wasn’t.

This defeat, along with a number of other epic failures in my career, add up to bolster the popular argument that I should minimize the chance of pain and defeat by keeping my expectations low.

This strategy of operating with low expectations is employed by many. The thinking goes that if you don’t get your hopes up about something, then you won’t be as disappointed if it doesn’t work out. And if it turns out well, you’ll get the enjoyment of being pleasantly surprised.

As it turns out, it’s a flawed strategy.

According to neuroscientist Tali Sharot, people with high expectations always feel better, because how we feel depends on how we interpret the event.

When a person with high expectations succeeds, they attribute it to their own traits. When they fail, it wasn’t because they were dumb, it was because the exam happened to be unfair and next time they’ll do better. When a person with low expectations fails, it was because they were dumb, and if they succeed, it’s because the exam happened to be really easy and next time reality will catch up with them.

Secondly, regardless of the outcome, the act of anticipation makes us happy. It’s why people prefer Friday to Sunday, because it brings with it the anticipation of the weekend ahead.

Finally, optimism acts as a self-fulfilling prophecy. Believing we will be successful makes us more likely to be so, and optimism reduces stress and anxiety, leading to better health.

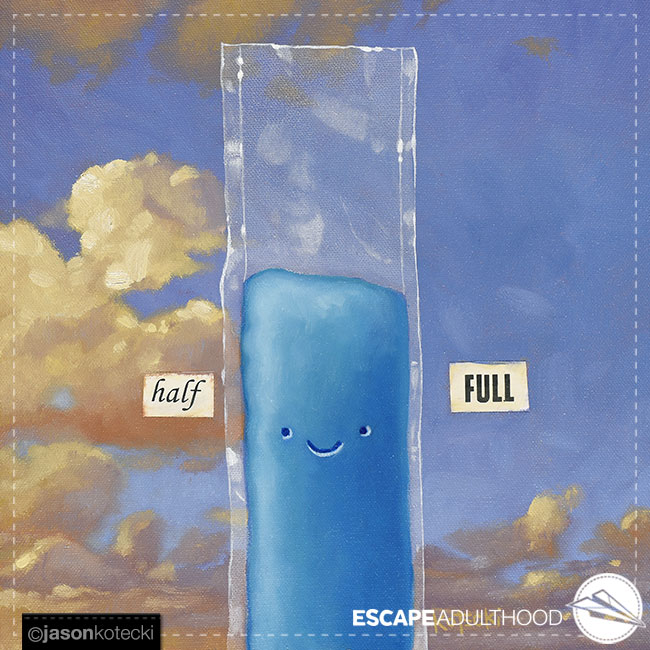

When a container is at 50% capacity, it is half full.

But technically, it’s also half empty.

Both are absolutely correct assessments of the container in question.

If the label you give it is completely subjective, go with the one that gives you the best chance of going somewhere beyond what you thought was possible.

So many of our experiences in life could be seen in the same light. We lose a job. We break a leg. We get dumped by the one we thought was The One. Is that unexpected, unwelcome thing that just happened in your life an obstacle or an opportunity?

Yes.

Both are absolutely correct assessments of the event in question.

Deciding what you call it can make all the difference.

Was Penguins Can’t Fly a failure?

Upon further review, believing that it had a chance at being a bestseller led us to put in a lot of effort. It pushed us to think of new and creative ways to promote it, and it got me out of my comfort zone in asking for help. All of these things made a difference. No, it wasn’t a NYT bestseller, but three printings later, and after having outsold my advance (something most published authors never do), it was a success.

It turns out that optimism attributed to that success. Without it, I would have always wondered what might have been.

I don’t know if I’m naturally optimistic or not. These days, even though I still feel fearful about getting my hopes up only to have them dashed, I’m realizing it’s more of a choice than a disposition.

We all get to make that choice every single day. To me, there’s really no contest.

I choose half full.

Jason, this post reminded me how much everyone enjoyed Penguins Can’t Fly when I gave copies as Christmas gifts. And the timing is perfect–because I’m putting together door prizes for some health fairs at work next month, and I can’t think of anything more conducive to health than curing adultitis! Fortunately, Amazon had them on hand, so I can get them in time. :-) Thanks for all you do to make the world a brighter place!

Pat

Thanks Pat! We appreciate your support in spreading the message!